Automobiles through the Decades Part 3: 1930 to 1939 When Crisis Sparked Creativity

The 1930s remain an age of automotive contradictions and innovation. Known as the Depression Era, this period was deeply scarred by economic collapse and widespread hardship, yet it nevertheless witnessed remarkable achievements in automotive engineering and design. Technical innovations paired with the elegance of Art Deco styling produced some of the era's most distinctive and memorable vehicles. Our collection includes remarkable examples that tell this story of resilience, ingenuity, and the relentless pursuit of progress against overwhelming odds.

The aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash changed the Auto industry forever. Sales, which peaked at approximately 5.3 million vehicles in 1929, plummeted dramatically. Production reached its lowest point in 1932 with only 1.3 million vehicles manufactured. Even by decade's end in 1939, sales had recovered to just 3.6 million vehicles. It would take a full twenty years for the industry to return to its pre-Depression sales levels.

The human cost was even more staggering. Ford Motor Company's workforce shrank from 128,000 employees in spring 1929 to just 37,000 by August 1931. Many iconic manufacturers, both large and small, did not survive. Notable brands that ceased production during the decade include Franklin (1934), Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg (1937), Pierce-Arrow (1938), and Stutz (1939). Only the strongest companies, General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, Hudson, Nash-Kelvinator, Packard, and Studebaker managed to endure. Survival required decisive action. As an example, General Motors responded swiftly by mothballing plants, reducing production, and lowering Chevrolet's breakeven point by a third. The company aggressively cut prices, and with their diversified brand strategy, GM was able to remain profitable every year throughout the Depression. Those companies with weaker balance sheets simply vanished.

Yet amid this devastation, the decade opened with traditional automotive design still dominant, only to witness its complete transformation by 1939. Perhaps no vehicle in our collection better illustrates this shift than the 1934 Chrysler Airflow. When Chrysler engineers began using aircraft wind tunnels to test automobile designs, they made a startling discovery: most cars were more aerodynamic driving backwards than forwards! The Airflow's revolutionary streamlined design reduced drag by nearly 50 percent, improved fuel economy, and increased top speeds. The design also experimented with unibody construction that would not become mainstream for another 30 years. Also Ride and handling improved dramatically as engineers moved the engine and passengers forward, creating better weight distribution and more even spring rates. While the public initially rejected its radical appearance, leading to poor sales, the Airflow established aerodynamic principles that every modern car employs today.

Our 1937 Cord 812 "Sportsman" Convertible Coupe represents another quantum leap forward. It was such a sensation at the 1935 NY Auto Show, that attendees stood on the bumpers of nearby cars to get a look. The Cord brought front-wheel drive to American luxury automobiles, a configuration that improved traction and handling while allowing designers to create lower, sleeker profiles without a driveshaft tunnel intruding into the passenger compartment. The Cord also introduced concealed retractable headlights, operated by elegant dashboard-mounted cranks—a feature that wouldn't become commonplace until the 1960s. With its coffin-nose design and art deco styling, the Cord looked like it belonged in 1950, not 1937.

Despite economic collapse, the Depression spurred manufacturers to create their most ambitious vehicles. If you were going to survive, you either built basic transportation for the masses or ultra-luxury automobiles for those still wealthy enough to afford them. The middle ground vanished. The 1937 Packard Twelve 1507 Formal Sedan exemplifies this approach perfectly. Packard's V12 engine delivered 175 horsepower with remarkable smoothness, representing the pinnacle of American luxury engineering. The company's famous slogan "Ask the man who owns one", suggested a level of satisfaction that transcended mere transportation. These were the cars of presidents, movie moguls, titans of business, the elite, and the notorious. The one in our was ordered new by comedian Jack Benny! At a time when most Americans struggled to afford necessities, Packard proved there was still a market for excellence without compromise.

The 1930s saw automotive design emerge as a distinct artistic discipline. Our 1934 Brewster-Ford Town Car represents coachbuilding's final golden age, when custom bodies were still crafted for discerning clients. While the 1934 Pierce Arrow Model 836A showcased integrated fender-mounted headlights that became a Pierce Arrow signature, blending functionality with distinctive style.

Beyond the showroom glamour, the 1930s introduced fundamental engineering improvements that made cars safer, more reliable, and more enjoyable to drive. Hydraulic brakes replaced mechanical linkages, providing more reliable and powerful stopping ability crucial as engines grew more powerful and speeds increased. Independent front suspension abandoned rigid front axles, allowing each wheel to respond independently to road irregularities. This dramatically improved both ride comfort and handling, making cars more controllable at higher speeds while providing passengers with a smoother journey.

All-steel body construction replaced wood-framed bodies, improving safety, durability, and enabling the complex curved designs that defined the era's aesthetic. This transition required revolutionary changes in manufacturing. Steel companies developed massive hydraulic presses and hardened dies capable of stamping thousands of parts, while Edward G. Budd's "shotweld" technique solved the challenge of joining steel without damaging its properties. Though tooling required high upfront investment, the per-unit cost became remarkably low at volume. The results were transformative: all-steel bodies were only 10 percent heavier than wooden cars but far safer and more durable. Steel's malleability enabled aerodynamic designs impossible with wood, while one press operator could now produce what previously required multiple skilled craftsmen.

Synchromesh transmissions revolutionized the driving experience. In earlier transmissions, shifting meant forcing gears spinning at different speeds to mesh, causing grinding and wear. Drivers had to "double clutch", pressing the clutch, shifting to neutral, releasing the clutch to match speeds, then clutching again to complete the shift. This required skill and practice. Synchromesh added synchronizers that used friction to match gear speeds automatically before engagement. Drivers could now simply press the clutch once and shift smoothly. What had been a skillful art became a simple action, democratizing the automobile for everyone.

The 1930s automotive story is ultimately one of human determination in the face of overwhelming adversity. In stark contrast to the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties, this decade brought widespread hardship, environmental disasters, and economic collapse. Yet faced with catastrophe, the engineers and designers who survived didn't retreat, they innovated with unprecedented creativity. The streamlined bodies, advanced suspensions, and powerful engines developed during this decade laid the foundation for modern automotive design. As this dramatic transformation reshaped the industry and a new light has shined on our question

“Did society shape the car or did the car shape society?” further complicating its answer. The Depression forced a brutal Darwinian selection: manufacturers either adapted quickly or disappeared. Those who survived did so by combining ruthless business decisions with inspired engineering and design.

As the decade ended, however, the innovations developed to survive the Depression would take on new significance. With enormous threats looming in the mid-1930s and war spreading throughout Europe and Asia by decade's end, the federal government began preparing for potential conflict. Roosevelt launched a limited preparedness campaign and in 1938 Congress authorized, the Defense Plant Corporation, which had the task of expanding production capabilities for military equipment. Companies began producing war materiel for European countries and the very manufacturing capabilities that had been refined during the Depression, the massive hydraulic presses, the precision stamping dies, the efficient assembly line techniques, were being eyed for an entirely different kind of production. The automotive industry's hard-won expertise in mass-producing complex steel structures would soon prove valuable in ways no one had anticipated when the decade began.

Our collection captures this pivotal moment when automobiles transformed from mechanical conveniences into sophisticated machines that balanced performance, safety, comfort, and beauty. The Depression-era cars in our museum aren't just survivors of a difficult time; they're testaments to what human ingenuity can achieve even in the darkest circumstances. They represent both the casualties of economic collapse (Pierce-Arrow, Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg) and the triumph of companies that emerged stronger through adaptation.

Visit us to see these remarkable machines up close and experience the decade that changed automotive history forever. And join us next month when we explore the 1940’s and their impact on the Automotive industry.

Automobiles through the decades Part 2: 1920 to 1929 The Roaring 20s

The 1920s, famously known as the Roaring 20s, began with the adoption of two pivotal amendments to the United States Constitution that would reshape American society. This vibrant era was characterized not only by the energetic rhythms of jazz music and the spread of modern ideas in bustling urban centers, but also by profound, quieter shifts occurring across the nation.

With the ratification of the 19th Amendment, women gained the right to vote and soon sought additional forms of independence, most notably the ability to drive. Freed from reliance on public transportation or male relatives, women embraced the automobile as a symbol of autonomy. Cars enabled them to travel independently for work, education, or leisure. The rise of women’s motor clubs, female stunt drivers, and racers underscored a new wave of empowerment and mobility for women. This spirit is epitomized by Mariette Hélène Delangle (also known as Hellé Nice), a French dancer who became a race car driver. She competed in many events and quickly became a household name in France.

One vehicle that encapsulates this transformative period is the 1928 Franklin Airman Sport Tourer, now preserved at the Tucson Auto Museum. With its sleek, lightweight construction and advanced technology, the Franklin especially appealed to women who were new to driving. It featured an air-cooled engine, easy gear shifting, and a comfortable design, making the car both accessible and inviting. Automobile manufacturers began marketing cars as symbols of possibility and self-determination, rather than mere mechanical strength. This surge in female independence on the road mirrored another revolution taking place across America’s backroads.

During the Prohibition era, which began with the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1920, a different story unfolded. Instead of curbing alcohol consumption, Prohibition spurred a thriving underground economy and introduced the bootlegger, a daring new type of driver. Men and women alike navigated rural roads in modified vehicles, evading law enforcement under the cover of darkness while transporting cars packed full of illegal goods. These drivers relied on skill and specially tuned vehicles that appeared “stock” but concealed enhanced suspensions, powerful engines, and hidden compartments for smuggling. When not fleeing authorities, many bootleggers raced each other on improvised tracks. Necessity became sport, laying the foundation for a unique American racing culture. This rebellious spirit would echo decades later in professional racing, epitomized by legends such as Dale Earnhardt. The #3 car on display at the Tucson Auto Museum pays tribute to this legacy.

Automobiles in the 1920s were also intertwined with themes of power, extravagance, and status, especially among movie moguls, titans of business, the elite, and the notorious. While bootleggers sped along remote routes, city streets showcased the opulent Duesenberg, a masterpiece of engineering. The Duesenberg stood in stark contrast to the flapper’s vehicle of freedom or the bootlegger’s workhorse, representing the pinnacle of luxury and distinction. Despite their differences, each of these vehicles played a role in shaping the era.

The Tucson Auto Museum's 1929 Duesenberg Model J Arlington Sedan is a perfect example of this American automotive icon. First, there was the raw power of the vehicle. The Duesenberg-designed straight 8 engine, with dual overhead cams, generated 265 horsepower, a setup that would be considered exotic for decades to come. In comparison, Model A Fords puttered around with a mere 40 horsepower. While the Big Three moved toward mass marketing and manufacturing with limited options, Duesenberg still allowed buyers to purchase a bare chassis and running gear. Owners then went to a third party for custom coachwork, and at that point the sky was the limit. However, this luxury did not come cheap; a car like that could cost upwards of $13,000, compared to the Ford Model A at $500.

Behind the scenes of newfound freedom, intrigue, and status, the automobile industry experienced explosive growth. Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler emerged as the “Big Three” auto manufacturers, transforming cars from luxury items into household necessities. In 1920, there were over 90 automobile manufacturers in the United States. By 1929, the Big Three controlled over 75% of the market. While consolidation brought efficiency and lower prices, it also meant less diversity in design and fewer choices for consumers seeking something unique.

New businesses sprang up to serve the increasing number of motorists, including gas stations, car repair shops, motels, convenience stores, and roadside restaurants. Technical innovations flourished—most notably, the four-wheel hydraulic brakes developed by Duesenberg, which were widely adopted by the late 1920s. Open touring cars gradually gave way to closed body styles, providing better protection from the elements and greater comfort for year-round driving.

The Tucson Auto Museum’s collection is more than a display of vintage cars; it preserves fragments of a broader American story. Each vehicle reflects the ambitions and experiences of individuals who shaped the nation’s future, whether young or old, law-abiding or rebellious, cautious or daring. The automobile stands as a vessel of change—a monument to freedom, risk, and the journey that shaped American society. Standing beside Dale Earnhardt’s #3, admiring the polished lines of the 1928 Franklin, or imagining a gangster cruising in a gleaming Duesenberg, it’s clear these machines are more than mere vehicles. They are storytellers—silent engines of transformation and lasting monuments to the spirit of the road. That spirit would face its greatest test in the decade to come. Next month we will look at the 1930’s, we will examine how the automotive industry navigated the Great Depression and adapted to the growing clouds of war.

Automobiles Through the Decades - 1910 to 1920: America Gets Its Wheels

Over the next several months, we will embark on a century-spanning journey through the Tucson Auto Museum’s collection. Each decade from 1910 through 2010 will be examined to answer one of automotive history’s most puzzling questions: Did society shape the car, or did the car shape society? I’ll give you a little hint—the answer is both, and the story of how is more fascinating than you might expect.

TAM’s 1913 Model T

In the second decade of the 20th century, America was quite literally on the move. From dirt wagon tracks to the beginnings of a national highway system, a growing population was discovering the freedom of the open road. At the heart of this transformation stood one car: the Ford Model T. The 1913 Touring car in our collection is proudly displayed at the Tucson Auto Museum (TAM). It is more than just a vehicle; it is a rolling artifact of how the automobile reshaped American life.

This pioneering vehicle wasn’t just a car; it was a machine designed for accessibility. When Henry Ford implemented the moving assembly line in 1913, the price of the Model T dropped significantly, putting car ownership within reach for many working Americans. Ford's system transformed car manufacturing from a craft into an industry, reducing production time from half a day to just 1 1/2 hours. TAM’s example reflects this simplicity—an engineering philosophy that helped democratize travel.

While the Model T made ownership possible, its success wasn’t just about affordability. Standardized gasoline-powered internal combustion engines had by then proven superior to steam and electric rivals, thanks to their greater range and convenience. Innovations in ignition systems, multi-cylinder layouts, and improved carburetors made cars more dependable, and the Model T benefited from every bit of that progress.

With more Americans climbing behind the wheel, ride comfort became important so that Americans would enjoy the drive and use them regularly. Pneumatic tires—air-filled rubber marvels—replaced solid wheels. Suspension systems, including early versions of shock absorbers and trusty leaf springs, did their best to keep passengers comfortable on often-unpaved roads. Alongside the scarlet Touring car, the Museum’s early vehicles reflect a moment when cars were transitioning from daring adventures into daily tools.

As Americans embraced their newfangled machines, society scrambled to create rules for this brave new world. As cars became a fixture of American life, towns and cities grappled with an entirely new set of challenges, “The Rules of the Road”. Imagine a world in which there are no stop signs, no traffic lights, and no speed limits. This was the world before 1910. All these things and more had to be developed to regulate the automobile. These early steps foreshadowed the more sophisticated road rules to come, as society raced to keep up with its new machines.

And race it did. In 1913, there were about 1.3 million vehicles on American roads; by 1920, that number had exploded to over 8 million. The cultural and logistical impact of this boom was staggering. Roads were improved, thanks in part to the “Good Roads Movement,” which was supported by automakers and bicyclists alike. With the growth of car dealerships, financing plans emerged, fostering a true consumer marketplace for vehicles. Through the lens of TAM’s early automobiles, particularly this Ford icon, visitors can trace not just mechanical innovations, but the beginnings of a cultural transformation.

Yet not all the changes were positive. As cars proliferated, so did accidents. Between 1910 and 1920, child fatalities from automobile accidents were alarmingly common. Though exact statistics are difficult to come by, studies show that in cities like New York and Chicago, automobiles quickly became a leading cause of death among children. In the absence of modern traffic laws and pedestrian safety measures, young lives were often lost in tragic encounters with the new machines barreling down city streets.

Amid these sweeping societal shifts, the Model T’s design was evolving too, but not always in the way people expect. The myth that all Model Ts were black stems from the period between 1914 and 1926, when Ford limited paint options to black. The reason for the change to all black only is debated in history. The commonly accepted reason is that black was the only color that dried fast enough to keep up with the assembly line. This makes sense from a timing perspective. But cost of the paint, operation efficiency and durability are also potential reasons for the limitation after 1914. Earlier models, including the Tucson Auto Museum’s 1913 Touring car, came in a variety of colors. Ours is red, which is likely NOT the original color. The only standard color available in 1913, a year before the black-only mandate was handed down, was a dark blue. While a few T’s went to market dressed in other colors that year, it is unlikely ours was originally red. Prior to 1913, red, green and gray were common.

Taken together, these innovations and transformations represent more than a leap in transportation technology. They tell the story of America coming into its own, one wheel at a time. And the next time you see TAM’s scarlet Touring car gleaming under museum lights, remember you are not just looking at a car, but at the nation’s first steps toward modern mobility and those steps would soon break into a full sprint in the decade to come.

One Man and His Plan - Part Three: John D. Delorean and his time-traveling wonder

Part three of TAM’s series of articles about incredible visionaries and their cars that were meant to revolutionize the automotive industry but failed.

John DeLorean: The Rise, Fall, and Silver Screen Resurrection of a Dreamer

Few figures in automotive history have captured the imagination quite like John Z. DeLorean — the maverick engineer, executive, and visionary who dared to challenge Detroit’s status quo. His story is a blend of brilliance, ambition, controversy, and redemption — a real-life drama that could only end with his car becoming a Hollywood legend.

The Golden Boy of General Motors

In the 1950s and ’60s, John DeLorean was one of the brightest stars in the American auto industry. A gifted engineer with a flair for marketing, he rose quickly through the ranks at General Motors. By age 40, he was the youngest division head in GM history, credited with creating one of the most iconic muscle cars ever built: the Pontiac GTO.

But DeLorean was never a typical corporate executive. With his tailored suits, long sideburns, and celebrity friends, he looked more like a movie star than an engineer. He dreamed of doing things differently — of building a car company that valued innovation, safety, and design over conformity and cost-cutting.

The Dream of the DMC-12

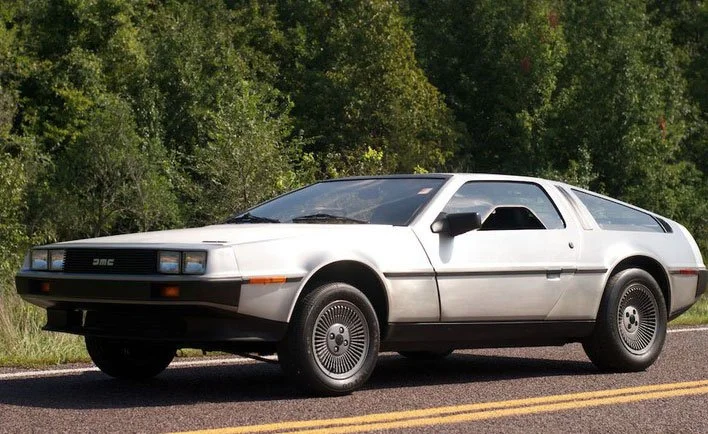

In 1973, DeLorean left GM to chase his vision: to create the world’s most advanced sports car under his own name. The DeLorean Motor Company (DMC) was born. His car, the DMC-12, featured a stainless-steel body, gull-wing doors, and a futuristic wedge-shaped design that turned heads everywhere it went.

Production began in 1981 in Northern Ireland — a bold move fueled by government subsidies and DeLorean’s relentless optimism. But the dream soon collided with harsh realities. Manufacturing delays, cost overruns, and a global recession plagued the project. The car’s performance didn’t match its looks, and the company teetered on the edge of financial ruin within a year.

Scandal and Struggle

In 1982, just as DMC was collapsing, DeLorean was arrested in a high-profile drug trafficking sting, accused of attempting to finance his struggling company through cocaine deals. The shocking images of the once-celebrated executive in handcuffs seemed to mark a tragic end.

However, in 1984, DeLorean was acquitted of all charges, after successfully arguing that he had been entrapped by government agents. Though legally vindicated, his reputation and company were beyond repair. The DeLorean Motor Company folded, leaving behind roughly 9,000 cars — and a legacy of “what could have been.”

Back to the Future — Literally

Just a few years later, DeLorean’s dream car found new life in the unlikeliest of places: Hollywood. When “Back to the Future” premiered in 1985, the stainless-steel DMC-12 became the world’s most famous time machine. The film immortalized the car — and, by extension, its creator — as symbols of innovation and imagination.

Today, surviving DeLoreans are prized collector’s items, with dedicated clubs and restoration shops keeping them on the road. The car’s blend of 1980s futurism and movie magic continues to captivate fans around the world.

A Legacy Forged in Steel

John DeLorean’s story is one of ambition and audacity — proof that chasing a dream can sometimes come at great cost, but can also leave an indelible mark. His stainless-steel sports car may have failed as a business venture, but it succeeded in becoming an icon. In the end, DeLorean achieved what few ever do: he built something unforgettable.

🚗 Museum Connection

At the Tucson Auto Museum, we celebrate visionaries like John DeLorean — people who refused to accept “the way things are” and instead reshaped automotive history through sheer determination. While we don’t all get to travel through time in a stainless-steel car, we can travel back in time by exploring the design, engineering, and spirit of innovators like DeLorean inside our galleries. Our 1981 example of the Delorean captures the spirit and excess of the ‘80s.

🕒 Did You Know?

Only about 9,000 DeLoreans were built — and more than 6,000 still exist today, thanks to dedicated owners and parts suppliers.

Every DeLorean left the factory unpainted, showing off its brushed stainless-steel panels.

The car’s gull-wing doors were designed by the same engineer who helped develop the Mercedes 300SL’s doors in the 1950s.

A new company in Texas is now reviving the DeLorean name with modern electric concepts inspired by the original DMC-12.

One Man and His Plan - Part Two: Earl “Madman” Muntz and his Muntz Jet

Part 2 of TAM’s series exploring the audacious failures in the history of the automotive industry is a fun read. Enter the “mad” world of Earl Muntz,..

Earl “Madman” Muntz: The Car Salesman Who Tried to Out-Cadillac Cadillac

If Elon Musk and P.T. Barnum had a child in 1914, and that child grew up with a fondness for convertibles, televisions, and outlandish advertising stunts, you’d get Earl “Madman” Muntz. A larger-than-life pitchman, tinkerer, and self-taught engineer, Muntz is one of those glorious characters in American history whose name should be better known. Not because everything he touched turned to gold—quite the opposite, in fact. He’s remembered because he thought big, crashed hard, and did it all with a grin.

The Origin of the “Madman”

Earl Muntz started out selling used cars in the 1930s and ’40s, where he quickly realized that bland pitches don’t move metal. He slapped on a nickname—“Madman”—and ran loud, outrageous radio and newspaper ads that made him sound like he’d lost his marbles. His slogan was simple: prices so low, he must be insane! Crowds loved it. In an era when car dealers were stiff and serious, Muntz leaned all the way into carnival-barker energy.

He wore outlandish suits. He shouted about bargains. He plastered “Madman Muntz” everywhere. The gimmick worked so well that by the mid-1940s, he was one of America’s best-known car dealers. And then he did something no one expected: he moved from hustling cars on the lot to building one of his own.

Enter the Muntz Jet

The Muntz Jet was born in 1950, a postwar fever dream made of chrome, horsepower, and audacity. Muntz bought the rights to a short-lived sports car called the Kurtis Kraft, stretched it into a four-seater, and gave it the kind of styling that screamed, “Hollywood leading man.” The Jet had sleek lines, a long hood, and was stuffed with luxury touches like leather interiors and even seatbelts—long before Detroit thought they were necessary. There was even a liquor cabinet in the backseat, because it was the 50’s and why not?

The performance? Depending on the V8 under the hood (Cadillac at first, Lincoln later), the Muntz Jet could hit 150 mph. That made it one of the fastest production cars in the world at the time. It was, in essence, America’s first personal luxury sports car, a genre that wouldn’t really take off until Ford birthed the Thunderbird and GM rolled out the Corvette.

But while those corporate giants had entire factories, Muntz had… a rented building, a small crew, and his own checkbook. And that’s where things went sideways.

Why the Jet Never Took Off

Each Muntz Jet cost about $6,500 to build. Muntz sold them for around $5,500. You don’t need an MBA to see the problem. For every Jet sold, Muntz lost money—up to $1,000 a pop. That’s a business model even Tesla might blush at.

Still, the Jet attracted celebrities like Mickey Rooney and Mario Lanza, and it became a status symbol for the Hollywood set. But by 1954, only about 400 Jets had been built, and Muntz pulled the plug before he went completely bankrupt. Today, surviving Jets are prized collectibles, valued as much for their rarity as for the sheer audacity of the man who built them.

Not Just Cars: The Other Madman Inventions

Muntz didn’t stop with cars. His knack for being just ahead of the curve (and sometimes tripping over it) showed up in other industries:

Television: Muntz launched a line of affordable TV sets in the late 1940s, bringing the boob tube to middle-class living rooms before RCA or Zenith could dominate. He was credited with “Muntzing,” a process of simplifying electronics by stripping out non-essential parts to cut costs.

8-Track Precursor: He marketed the “Muntz Stereo-Pak,” a 4-track car stereo system that directly inspired the 8-track cartridge format of the 1960s. For a while, if you wanted to blast Sinatra in your convertible, you probably had Muntz to thank.

Why We Love the Madman

Was Earl “Madman” Muntz a genius? A huckster? A visionary? The answer is yes. He embodied a uniquely American mix of optimism, bravado, and disregard for balance sheets. While his Jet was a commercial flop, it paved the way for the idea that an American sports-luxury car could compete with Europe’s best.

Today, when you see a Muntz Jet, you’re not just looking at a car. You’re looking at the physical embodiment of a man who refused to think small. A man who believed that if you shouted loud enough, believed hard enough, and chrome-plated enough, you could bend the market to your will.

It didn’t quite work. But it sure was fun to watch.

One Man and His Plan - Part One: Gary Davis and the Davis Divan

“One Man and His Plan” - Part One, Gary Davis and the Davis Divan. Jump into the first in a series of articles about past automotive visionaries and their unique contributions to technology, culture, folklore and more.

The Three-Wheeled Dream That Almost Was

The 1948 Davis-Divan. The first “production” Davis, now in the Tucson Auto Museum collection